Heritage, legacy, genetics . . . whatever you call it, or however you choose to look at it . . . is an important thing, and has always been profoundly important to me. I left out the most obvious word - family - because sometimes in this life, for various reasons, we choose to separate ourselves from the very foundation of who we are. It may be in our own best interests; it's most assuredly always in spite of ourselves. But I've come to understand that sometimes the healthiest thing, sometimes the only thing you can do, is to hold onto the best part of a person, acknowledging and honoring their part in your story, while keeping a distance. You can love them or hate them, or remain indifferent, but you can't deny them. Because whether it's in something as benign as the arch of an eyebrow, the gait of a stride, a passion for color, a predilection for Cilantro or whether it's reflected in the very essence of who you are - an ear for music, an inclination for mechanics, or a gift for healing, you can't escape your DNA. So you might as well make friends with it.

The photograph at the top is of my great-grandmother and most of her siblings. It was taken around 1900 in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. To the far right is my great-grandmother, Nora Mae Jones, presumably the only blonde in the bunch, if it's not a trick of the light. In the faces of her siblings, I see the deep-set, steady gaze and the square jaws of my uncles, my cousins, my brothers. The boy at the top left is a dead ringer for my father around that age. And I can almost imagine my own features, and my daughters' mirrored in the face of Nora Mae. She lived for ninety more years after this photograph was taken, til just a few months before her one hundredth birthday, still picking the banjo and chewing tobacco. She had a holy side -- I can still remember her pointing a bony finger at the tv and declaring it the root of all evil -- but she could swear like a sailor in a fit of rage if you made her angry. She outlived my great-grandfather, Charles Hendrickson Ditmore, by about twenty years.

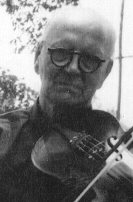

Charley's family was from the other side of the mountain, in Tennessee's Cade's Cove, said to be an enclave for Southern Abolition during the Civil War. The whole story of his grandparents during that time (my great-great-great grandparents) is as hazy and as cryptic as the photographs (below). But based on conjecture, it's interesting to imagine how their struggles as "rebels among rebels" must have been, fighting and living and dying and raising babies and losing babies in one of the most beautiful and holy places on Earth. It must have crushed their spirits and built their fortitude over and over again. Charley was born there, too. He died in 1967, the year I was born. I didn't know him, but I have a picture of him playing a fiddle and this newspaper article.

Charley Ditmore shoots Pitt Rose 1923

Maryville Times, (Blount Co. TN) Monday, April 2, 1923:

“Killing Ends Old Grudge"---Pitt Rose was shot and killed by Charley Ditmore Saturday afternoon, one shot being in the neck and two in the back, the trouble occurring at Calderwood. Ditmore is now in jail, his preliminary trial having been set for Tuesday morning. He claims self defense. Esquires Jett and Brakebill will hear the case. It is said that an old grudge has existed between the men for some time, it being claimed that Rose accused Ditmore of having reported a still. It is asserted that Rose had threatened Ditmore, saying he would have to pay for the still or suffer the results. Parties from Calderwood asserted that Rose stepped in front of Ditmore Saturday and told him the matter would have to be settled then, and Ditmore fired three shots into Rose, one entering his neck and two his back as he fell. It was stated three bottles of whisky were taken from Rose’s pockets.

It's hard to imagine that that sweet looking old man whose legacy to future generations was the gift of music was also a murderer and a coward. But maybe that's neither accurate, nor fair. In order to really understand a person, you have to understand their culture and where they come from. Temperance, or Prohibition was a hot button issue, particularly in eastern Tennessee during that time. In 1920, Tennessee enacted state Prohibition even before national Prohibition was enacted into law by the 18th Amendment. It was a moral issue, but one that conflicted with the economy in a mountainous region that could sustain little industry. "Stilling" and selling alcohol was the only means of cash money that many could come by. Now I am not convinced that my great-grandfather was a teetotaler. Alcohol has been the catalyst for too many bad decisions throughout the history of my family. And I won't speculate about the validity or the absurdity of Pitt Rose's accusation. I don't know what that was all about. But what I can imagine is that my great-grandfather was not immune to the violent nature of a culture where the very livelihood of the people is being threatened. That he adopted a kill or be killed survivalist mentality. Which must have been the accepted standard of the day, because I never did hear that he spent any time in prison. Still, it must have been awkward for my grandfather, nine years old by my calculations, to have to sit next to Pitt Rose's children in school after that . . . "Sorry my dad killed your dad. . . " More speculation, but realistically, it had to have had some lasting impact on him. And it also begs the question of nature vs. nurture? What was in my great-grandfather's very nature that would allow him to do something so egregious? And at the end of the day, why was it Pitt Rose lying dead and not Charley? Is survival instinct something he passed on in his DNA, or just simply violence? I would assert that even in these more civil times, brawlers abound in my family. But we are also survivors. Sometimes sin is simply unacceptable; other times it's two sides of a coin.

There are people whose DNA I share with whom I choose not to actively participate with in a family unit anymore, and who would have to have a real, authentic come to Jesus for me to ever consider reversing my decision. But I don't judge them, and I don't hate them. It doesn't even mean that I don't love them. It just means that I choose to protect and preserve the family that I created. It means that I choose to honor myself, and in doing that, I embrace all the parts of me that come from them, and leave it up to God to heal the unacceptable. My husband and I err on the side of gun ownership, and in our circle of supporters, there is often debate about whether or not, in a situation where there was a very real threat to our lives, could we shoot to kill? I answer unequivocally, yes. DNA. Sometimes, in a fit of rage, I swear like a sailor and sometimes I drink too much. DNA. Sometimes I need a come to Jesus. DNA. I have been known to intimidate people unintentionally with an unflinching, steady gaze. DNA. I'm a quirky left hander. DNA. I have never stumbled upon any musical inclination, but somehow it showed up in my daughters, along with their father's chiseled Scandinavian bone structure, as well as his offbeat sense of humor (Kelsey) and his blonde gene (Brittany). DNA. I have a passion for language and for telling a story. I labor over the flow of the paragraph and the exact words. It keeps me awake at night. I don't know where this came from, but I know that some relative, near or distant, must share, or have shared, a hidden or dormant gene for written communication. And I delight in the fact that both of my daughters inherited it. DNA. I love unconditionally, and I forgive. . . . DNA . . . and a little bit of Jesus.