Exactly one year ago today I half fulfilled a dream to hike the Smoky Mountain region of the Appalachian Trail. I say half fulfilled because at 36 of the 72 miles in, I was done. It wasn’t the elevation or the distance or the heat or the rain, but from my first step onto that trail, I knew there was something wrong with my body. I’m a runner and I knew it shouldn’t have been that hard. I knew.

I was both profoundly disappointed in myself and too sick to care. Walking the Appalachian trail had long been a bucket list check for me, but it was something more, too. I had chosen this particular section of trail because it was part of my heritage. My grandfather had built roads up into these mountains . . . My great grandfather helped to build the dams . . . as well as the stereotypical culture of backwoods grit. My grandmother claimed Cherokee ancestry from here and she and her sisters carried it prominently in their features. I passed it on to my own daughters. I had imagined this hike as part of a Cheryl Strayed-esque healing journey . . . One carefully stitched together to fit my own particular set of sorrows . . . Pieces of the fabric clumsily thrown together as healing testament to my own fractured soul. In the two years leading up to it, I had separated from my husband and moved from Detroit to the west side of the state, living alone for the first time except for a matched set of sweet and irrepressible Boxers that I couldn’t bear to leave behind. I had removed myself from toxic relationships that demanded too much of me and offered little in return. I had taken up running, changed jobs three times until I found one to wake up for in the morning, changed my name, and eventually found a better home for the Boxers after accepting that they were too much for one person to handle in a small apartment. Every piece was a death and a rebirth. My soul was tired and lonely. I wanted to reconnect with myself, feel my strength resonating up from the ground I walked on, and know deeply that I had had come from someplace beautiful . . . hear from the physically beautiful people who stared out at me in photographs from loving eyes that looked like mine. I wanted to hear whispers of welcome home echo from the ancient forests and the rolling, misty ridges. Mostly, I just heard . . . From my own bones . . . I thought . . . Something. Is. Wrong.

And so I came home and saw a doctor . . . And another . . . And another. There were cancer surgeries that cut deeply into my body to leave permanent battle scars. Everything I didn't need was removed, and I very often I wonder if then some. There was chemotherapy that plagued me with strange maladies, and rogue, painful episodes of gallstones between that had nothing to do with cancer, but punctuated the ridiculousness of my situation with random waves of fresh hell. There were post op complications that included a lengthy bout with pneumonia and Covid tests that made me want to fight nurses. There was unprecedented isolation and spiraling loneliness . . . upon isolation . . . that would test even the most extreme introvert.

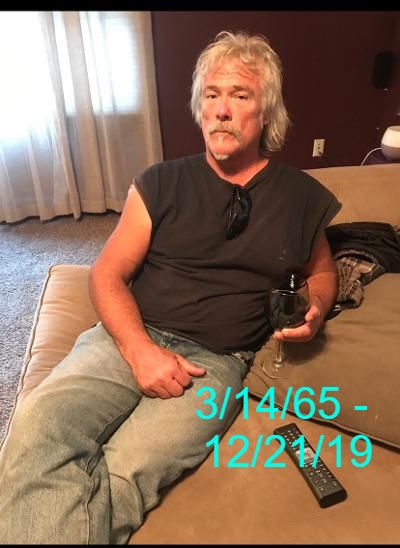

Within this same year I divorced and lost my brother to an illness that eerily mirrored my own. He died on December 21, just before Christmas, the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. I picked up his ashes in Detroit between surgeries and gallstone attacks and brought them home with me to West Michigan. There was no urn. They handed him to me in a box, and the irony was not lost on me. Another giant X checking the box on the absurdity of this life . . . my life . . . and mostly his. I brought him home with me and put the box in a corner just beyond my bookshelf . . . where my eyes don’t fall unless I’m vacuuming or dusting, or I needed to pluck my copy of Tolstoy’s War and Peace from a bottom shelf . . . I knew I would never read it. And even though my oldest daughter sent me a marbled blue urn that arrived just days after I told her this sad story, I put the urn on the top center of the bookshelf without ever transferring the ashes. I could look at the blue. It was the electric blue of his eyes that twinkled mischievously in his lucid moments. It was the cerulean glow of our favorite Christmas lights when we were children. It was the aqua expanse of water and sky where he was freest from the torment of mental illness that plagued him all of his adult life. I could look at the empty blue urn . . . I could not open the box.

But as my body has healed over these long months of isolation, so has grown my capacity, my strength for grieving. I walk my own trail, the North Country Trail that winds through Michigan just outside my door and I leak tears of grief and shock and even gratitude for what this past year has brought. I watch the flowers grow to their glory and die and they are replaced by new colors. And I ask my God what is one life to you? What is one death? He answers always: Everything . . . so I keep on living fiercely, intentionally.

Great and terrible things happen to me in the middle of July. But so far, this year, alone in a pandemic, everything is mundane. I’ll just sit with that thought for a moment . . . And wait. Every day I work a little, connect with people behind my screen, walk a little, plunge myself into a blue cool to wash away the dust, and welcome the sunset in a way I never have before. Before . . . sunsets from home were sharp and lonely. I used to expend all my energy trying to outsmart them. Come home late. Come home early. Close the blinds. Stay ahead of the lonely hurt in mindless activity. These days . . . These interminably long and hot summer days of pandemic . . . I turn my face into the sinking ball of light that first illuminates my west facing balcony, and then fades from electric blue into soft and fiery colors. It is a healing gift. I still myself in the call of the cicada that drones and dies. Fireflies signal the twilight, and the strength of starlight points finally send them home. In the predictable patterns of mid summer, there is no tragedy this year . . . No great triumph has happened, I think.

I celebrate July for whatever is to come by hiking my trail. I do my thing . . . with the pool and the dust and the sunset . . . And then, on this night, I stand in front of the bookshelf . . . take down my copy of Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods. I open it to the marked pages of where his journey falls in the exact place on that same stretch of that Appalachian Trail where I walked off exactly a year ago today. I laugh out loud as I read again Bryson describing the misery of his journey with great hilarious gusto and hyperbole, and I imagine my brother’s impossibly blue eyes, in a rare moment of joy, lucid and free, laughing at just the right part of my story. I need the strength of this remembering . . . this imagining . . . this moment . . . to hold power over the intensity of the same blue that implored me in his worst moment . . . Or was it mine? . . . when he said he didn’t want die . . . asked me to help him . . . When I looked away from his agony in horror and anger, sick myself, and thought . . . I can’t . . . anymore . . .

I hold on to the moment . . . and let go . . .

Before I can change my mind, l reach up and take down the urn. I take the urn and the box out to my balcony. I breathe in the balmy, earthy night air and carefully open the bag. I pour what’s left of my brother’s body into the blue and close the lid over it, noticing for the first time that the silver matching bands at the top and the bottom have flowers etched all around. Then I pour myself a glass of chilled Merlot, light some candles, and sit quietly with him for a while.

I think again, tonight, as I have every evening for the last eight weeks, that my body hurts a little less than yesterday . . . And so does my heart.

Someday l’ll take him back to the top of the mountain with me. I’ll hold handfuls of him tightly in a prayer and let the dust sift through my fingers, let the wind carry his DNA to mingle in the earth with our grandfathers and grandmothers and great grandfathers and great grandmothers. I’ll imagine them welcoming their same strength of his spirit and accepting their same brokenness.

But tonight, this is enough. I look out into the night, just over the blue, and I know that tomorrow, everything. . . everything . . . will hurt just a little less than today.